Naked Britannia: The Hidden Security Crisis Inside Britain’s Retrofit Revolution

The frontline is not where you think it is

A heat pump installer in Gateshead is now as important as an infantry soldier in Aldershot.

That may sound dramatic, but it is the honest shape of the world we have entered. The frontline has moved. It does not run along distant borders. It runs through the stud walls of British homes, along the cable routes in our attics, and inside the firmware of the systems we rely on for heat and power.

Retrofit has become a distributed battlefield where the foot soldiers are not wearing camouflage. They are consumers, electricians, plumbers, solar installers, heat pump engineers, assessors, and small contractors. Every time they mount an inverter, commission a heat pump, register a device to a cloud, or pair a smart controller, they are handling the modern equivalent of critical infrastructure.

The non commissioned officers of this domain are the installation firms and SMEs who interpret standards and keep the frontline moving. Above them stand the junior officers, the certification schemes and training bodies who shape professional behaviour. The colonels are the trade associations who negotiate with government. And the admirals who set national strategy are DESNZ, Ofgem, and the regulatory authorities who believe they are steering a domestic energy transition.

What almost none of them realise is that this is a new theatre of national defence.

And Britain is walking into it this battle without a stitch on - let alone a weapon to defend or attack.

The invisible infrastructure that now heats and powers Britain

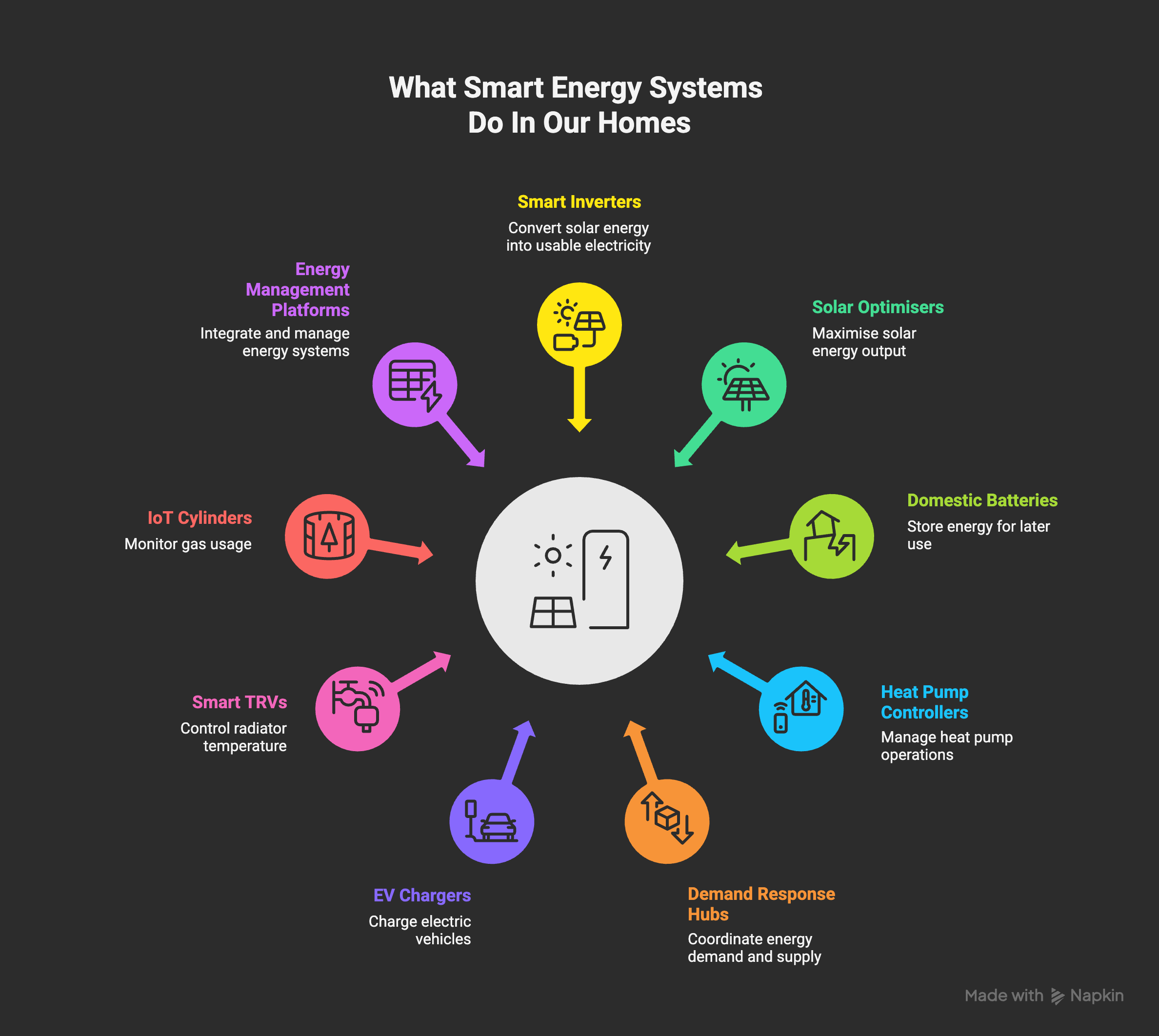

The infantry of retrofit work with tools that no longer behave like traditional hardware. Retrofit is now a software battlefield. The equipment entering British homes is part appliance, part server node, part dependent client of remote computing environments controlled abroad.

Frontline forces install these vulnerabilities into our homes ⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️

Each device calls home. Each device awaits orders from a server that may sit in California, or Guangdong, or Frankfurt. Each device relies on remote firmware updates that installers cannot inspect. Each device can be disabled or misdirected by commands they will never see.

This is an army without sovereignty. Equipment deployed in the field, but owned by foreign generals.

A nation that cannot inspect its own weapons cannot defend its own territory.

Today, Britain cannot inspect the firmware that runs its heating and energy systems.

China and America: the superpowers shaping the battlefield

Every military strategist knows that a small nation caught between great powers must design for resilience, not optimism.

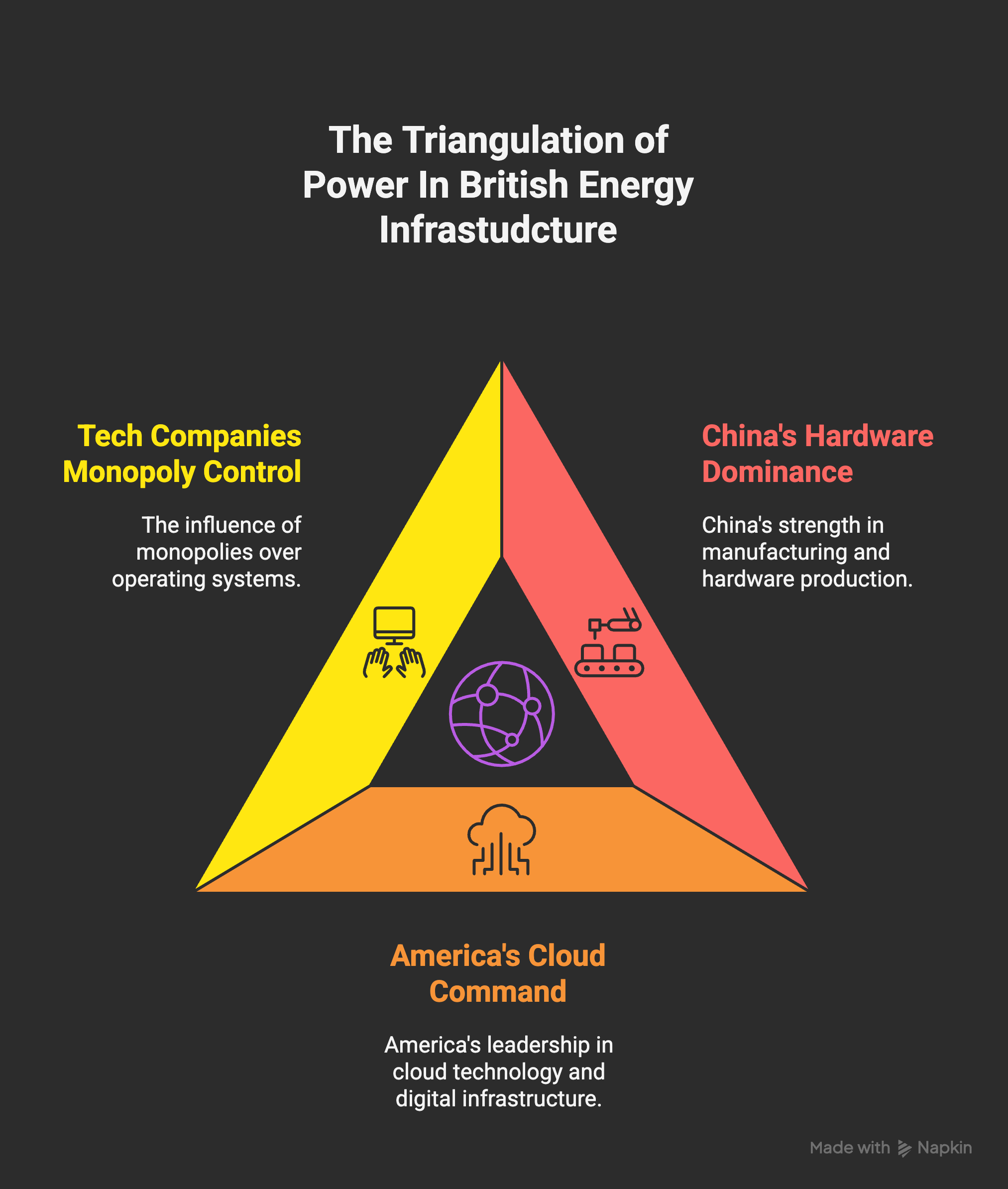

The China problem is familiar. China manufactures the vast majority of global energy hardware, from inverters and batteries to heat pumps and control electronics. It sets standards through sheer industrial weight.

China is the predictable actor on this field.

Its influence is obvious, widely discussed, and openly acknowledged.

America is the more disruptive one.

The United States is an ally, but it is no longer sentimental. It is competing, re-shoring, politicising supply chains, and treating energy technology as a lever of national advantage. American firms control the cloud and software layers that British systems rely upon:

• billing engines

• cloud management for home energy

• battery fleet orchestration

• smart heating platforms

• device registries

• remote command APIs

• firmware update paths

This makes American companies not vendors but commanders. British infrastructure now depends on American digital sovereignty.

When a superpower shifts direction, its allies feel the pull. Britain is not prepared for that pull.

The British home as a target in a silent war

In the past, an adversary who wished to destabilise a country targeted airfields or power stations. Today they would target the devices inside people’s homes.

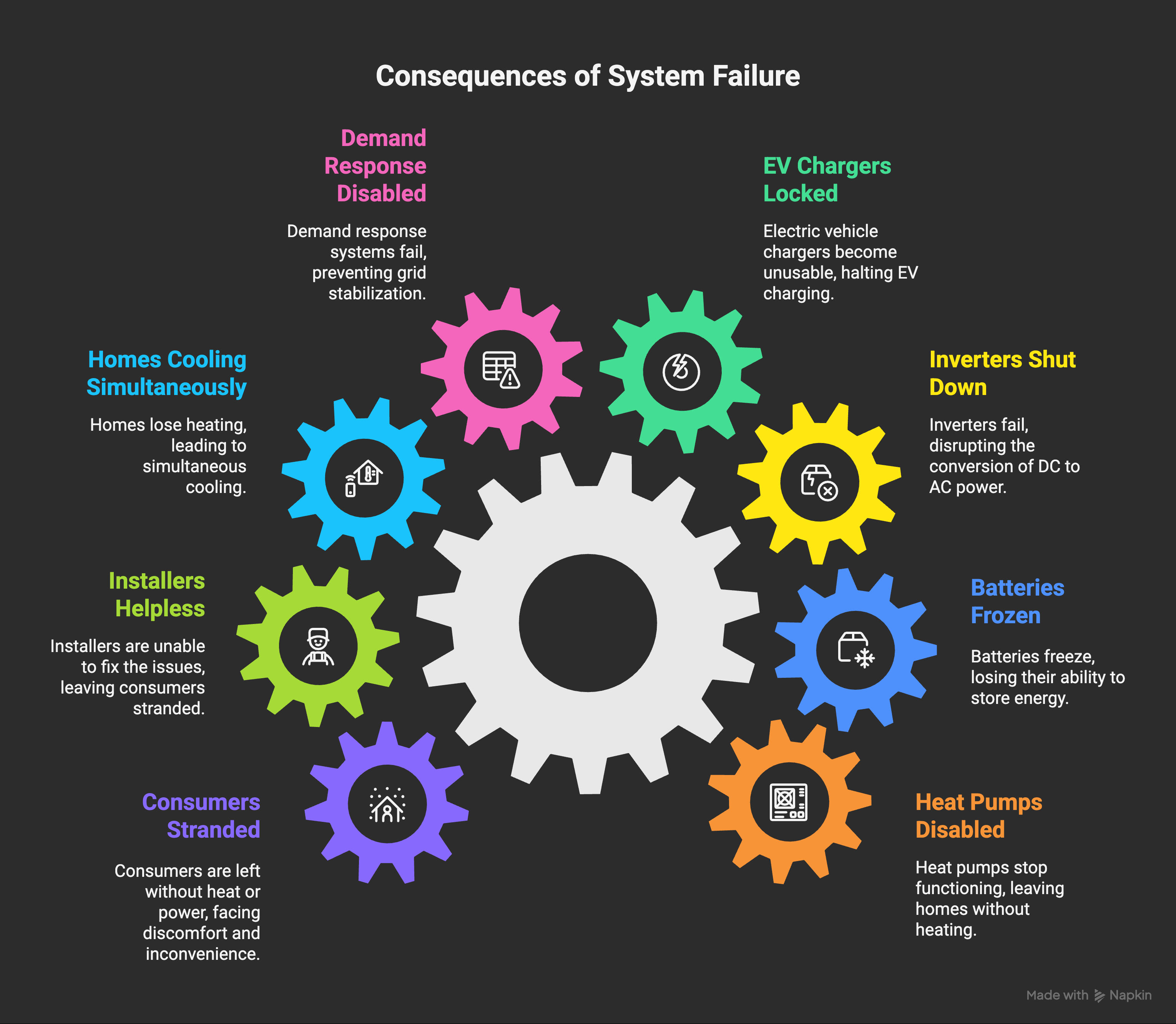

Millions of systems share identical control pathways. Identical APIs. Identical firmware lifecycles. Identical vulnerabilities.

A hostile actor would not need to breach the National Grid. They would strike a single OEM. Or a single server cluster. Or a device certificate authority.

Or a cloud authentication system.

The result would be the same ⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️

A bricked heating system is a strategic incident. A bricked fleet is national destabilisation.

The infantry would be the first to see it. Not ministers, not regulators.

Installers. Homeowners. The frontline.

The adversary Britain forgot - the monopolies the Marshall Plan tried to prevent

After the Second World War, American planners insisted that Europe build safeguards against concentrated corporate power. They believed monopolies distorted democracy and created conditions for extremism, Fascism. Competition law became part of Europe’s stabilising architecture.

Digital systems have quietly bypassed that architecture.

Energy hardware now depends on the operating systems, app stores, firmware pipelines, billing platforms, and cloud infrastructures of a small set of global corporations. Eight corporations, led by eight billionaires with different ideologies but shared incentives, now sit above nations in the command hierarchy of the digital world.

They do not need to conspire. Their business models pull in the same direction: more control, more scale, more dependency.

This is the monopoly threat the Marshall Plan sought to prevent. It has returned in a new form.

Not monopolies of steel or coal. Monopolies of firmware, update channels, device authentication, and cloud environments.

China commands the hardware. America commands the cloud. The monopolies command the operating systems.

This is the triangle of power Britain must now navigate. And Britain has no defensive capacity within that triangle.

The missing protections

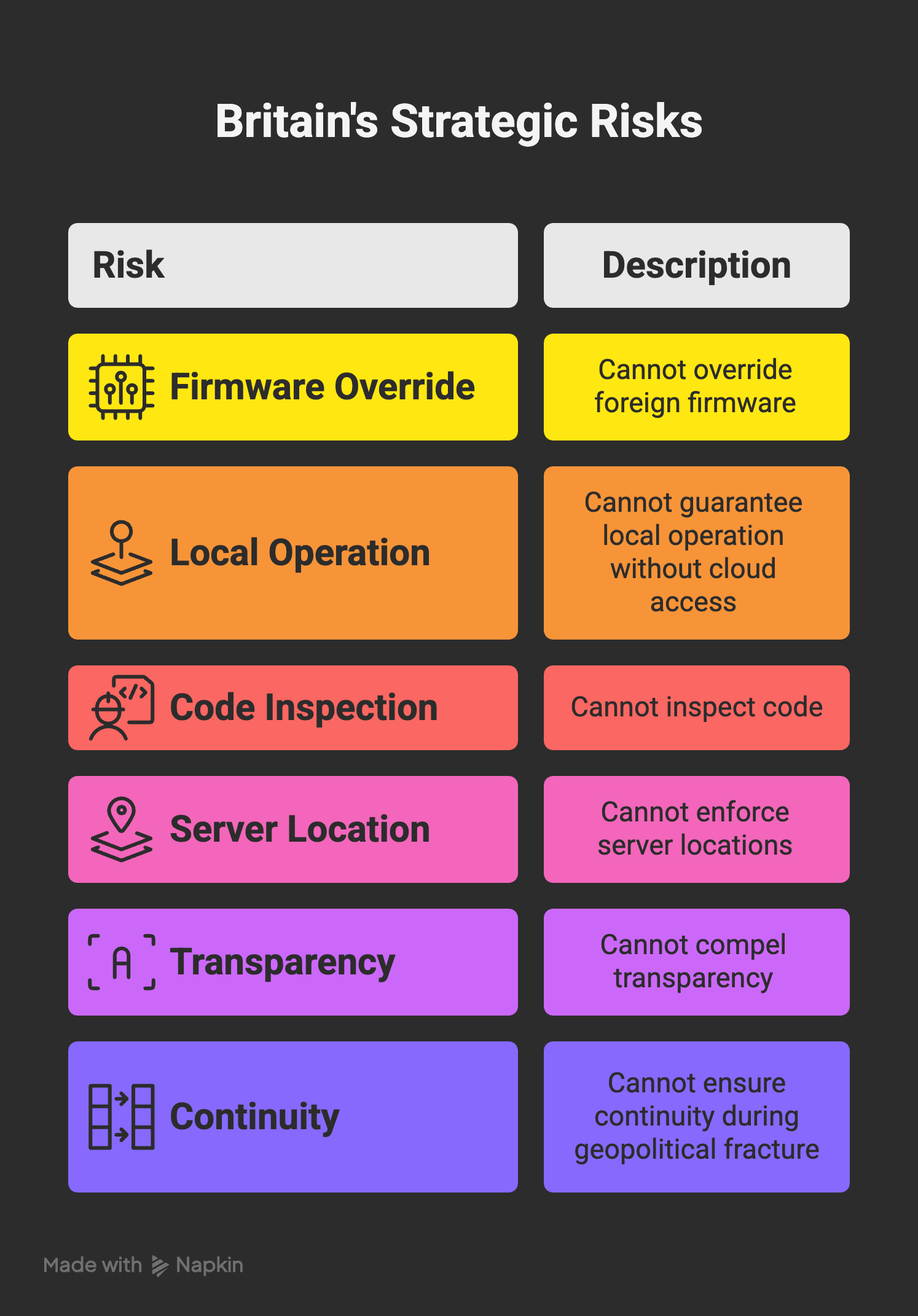

The infantry, the officers, the admirals, the homeowners, the entire chain of command, is marching into a future that has strategic risks they do not recognise.

This is the definition of a nation unprotected.

The devices in British homes may serve domestic purposes, but their sovereignty belongs elsewhere.

What Britain must build before it is too late

Britain needs strategy, not panic. Protection, not isolation.

Five principles should guide the defence of the home energy frontier:

1. Open firmware standards

No black boxes.

Independent inspection.

Mandatory transparency.

2. Local-first operation

Heating must heat.

Batteries must charge.

Solar must generate.

Even if every cloud server on Earth goes dark.

3. Jurisdictional control of critical systems

British homes should not depend on foreign servers for daily operation.

4. Mandatory vulnerability disclosure

Energy devices are infrastructure, not consumer gadgets.

5. A national cybersecurity doctrine for retrofit

Britain needs a defensive strategy equal to the scale of its ambitions.

The battlefield is domestic now

We are entering what tacticians would call an age of asymmetric conflict, where the advantage goes to whoever controls the smallest, most invisible points of failure.

A heat pump installer in Gateshead is as important as an infantry soldier in Aldershot because both now operate on a frontline that affects national security.

The British home is a node in a global system controlled by two superpowers and a handful of corporations. Retrofit is not only a decarbonisation effort. It is not only an economic programme. It is a distributed defence operation across millions of households.

Britain has exposed its soft belly. It has armed its infantry with equipment it cannot inspect. It has tied national comfort to foreign command structures. And it has walked into a new theatre of conflict any protection, weapons or in fact clothes on.

The future will belong to the nations that recognise this first.

Britain still has time. But not much.